Inflation and Interest Rates

December 20, 2021

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”- Mark Twain

Since the end of November, volatility in equity markets has increased markedly with sudden, sharp runups and declines becoming almost the rule.

Broad-based US Large capitalization benchmarks have advanced 2%-3% in the past two weeks, in spite of retreats in four of last week’s five trading sessions. International Developed and Emerging Markets indexes have, similarly, gained roughly 2%. Closing prices for the DJTMI since December 31, 2020, are below.

Source: Quotestream online quotation platform, www.quotemedia.com

Since November 6, small capitalization and value issues have weakened, creating a performance bifurcation within the equity markets. The YTD Russell 2000 illustrates this discrepancy.

Source: Quotestream online quotation platform, www.quotemedia.com

To be sure, the divergence comes amid a strong performance year for equities. Virtually every widely followed US benchmark is up 15%-20% so far this year, but small-cap and small value are well below their highest levels which, for the Russell 2000, represents a loss of roughly half its peak 2021 gains.

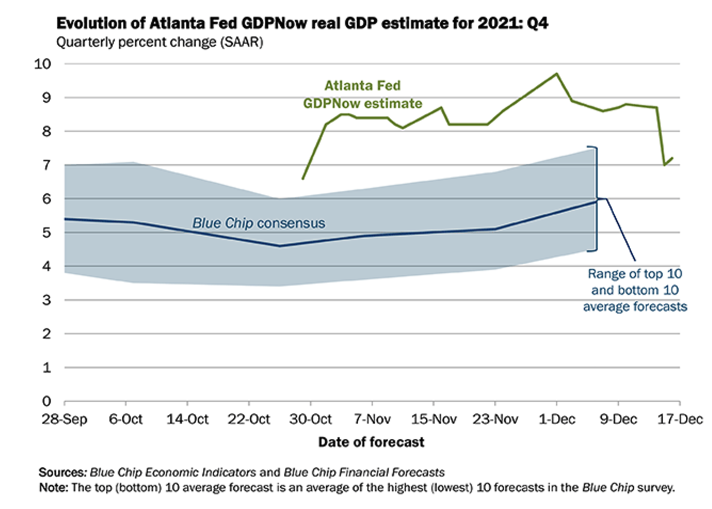

Earnings forecasts and expectations for the fourth quarter of 2021 remain optimistic. The Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank’s GDPNow™ tool is estimating solid growth as we close out the year. One caveat, however: Third quarter projections were similarly strong near September 30, but eventual annualized GDP growth was only 2%. Although only a handful of days remain in 2021, these numbers are volatile.

Inflation is on everyone’s mind, not least of all, Fed Chairman J. Powell, who is guiding the Fed’s response to 2021’s price uptrend. One of the Fed’s mandates is to maintain inflation within a 2%-3% band, which is far below the nearly 10% year-to-year increase in November’s Producer Price Index.[1] The CPI is rising as well but so far has not pushed above 7%.[2]

At Mr. Powell’s news conference after the conclusion of the FOMC’s December meeting, the Chairman announced an accelerated end to the Fed’s bond and mortgage-backed securities buying program. He also indicated three interest rate increases during 2022.[3] He further predicted a return to 2% inflation by the end of 2022.[4]

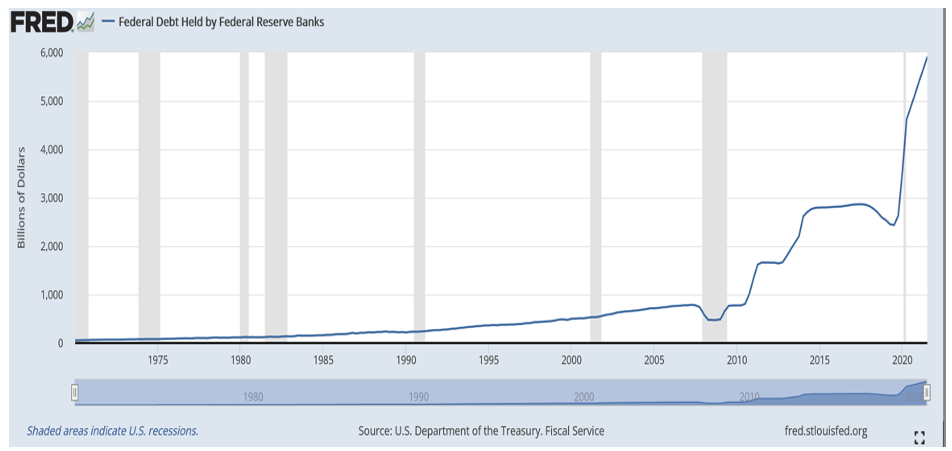

The Fed has facilitated an unprecedented expansion of deficit spending since 2010 and its balance sheet shows holdings of just under $6 trillion of Treasury paper on October 31, a figure that has increased by at least $200 billion since (as a result of continued bond buying).

In August 1979, President Jimmy Carter nominated Paul Volker to head the Federal Reserve. The nation faced a monetary situation similar to current circumstances with persistent rising inflation, sparked by an economy operating at total capacity and “easy money” from the Fed.

Wholesale prices were rising at a 14% annual rate by 1980, capping a long steady increase in the rate that had begun to creep above 1% in the mid-1960s with the funding of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs and the Vietnam War.[5]

The situation was exacerbated by a dramatic increase in energy costs resulting from the 1973 Arab oil embargo, imposed as retaliation for the US supporting Israel during the 1973-74 Yom Kippur War.[6] Then, as now, retail energy prices skyrocketed.

So, how did Mr. Volker attack inflation?

Volker redirected Fed policy from targeting interest rates to targeting monetary growth, which was the root cause of inflation (too much money chasing too few goods). His predecessors had pursued full employment as their sole mandate, accepting inflation as a price to pay. Keynesian monetary theory had been the go-to stimulative policy for decades, which suggested that government could tax and spend its way to full employment, disregarding inflation.[7]

The solution to too much money in circulation, was, obviously, to reduce the supply. The reasoning was if runaway money supply growth was fueling inflation, slowing the rate of growth would have an opposite effect.

Volker began draining banking system reserves and did not stem the resulting rise in interest rates. The Fed Funds rate eventually reached 20%, the prime rate 21%, mortgage rates soared to the mid-teens, and the country was plunged into recession from 1980-81.[8]

How did the Fed drain bank reserves? It sold Treasury instruments to banks, which reduced funds available for lending and slowed money growth to essentially zero.

The contrast with current Fed policy is stark. Instead of draining reserves, the Fed is augmenting them by purchasing bonds and mortgage-backed securities, increasing bank reserves, while holding interest rates well below the current inflation rate.

Mr. Powell will be buying credit instruments for the next 3 ½ months and only then will interest rates be allowed to creep higher. In the interim, it is likely that inflation will continue at recent levels, if not higher.

The Chairman is awaiting confirmation for a second term that begins next February. Until then, it appears he will not “rock the boat” with any more aggressive actions. Once reconfirmed, we suspect Powell may become a bit more determined, which is what will be needed to overcome inflation.

We don’t expect the FOMC’s current composition to support anything like Paul Volker’s draconian measures, but what is clear is that the Fed needs to stop buying bonds if it intends to quash price increases.

Finally, a word about Omicron/Covid. When the latest variant was identified in South Africa, roughly three weeks ago, many epidemiologists expressed the belief that, in line with previous viruses, this mutation would be more contagious but less lethal. At that time, it was universally agreed that more time was needed to evaluate the actual impact on public health.

As expected, cases have expanded exponentially in Europe after first appearing in Britain. Governments in Western Europe are beginning to revert to the same containment methods used last year. The Netherlands has instituted a full lockdown through January 14, and it would not be unexpected for other countries in the region to follow suit.[9]

In our view, markets face uncertainty over not only the lethality of Omicron, but also from a level of extreme vulnerability to government countermeasures.

Wringing inflation from the economy can be like ripping the band-aid off a wound if approached with history in mind: It will hurt but hopefully not for long. Whether the Fed pursues more aggressive inflation cures remains to be seen.

Historically, equities have proven the best method to outpace inflation. Investors with a long-term plan and coherent investment philosophy have little to fear from near-term market vicissitudes.

We will return in early January with the fourth quarter recap but until then, we wish all a Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays, and of course, a Happy and Prosperous New Year!

Byron A. Sanders

Investment Strategist

[1] “PRODUCER PRICE INDEXES – NOVEMBER 2021,: www.bls.gov, December 14, 2021.

[2] “Inflation surged 6.8% in November, even more than expected, to fastest rate since 1982,” www.cnbc.com, December 10, 2021.

[3] “Stocks Close Higher as Investors Welcome Fed Decision,” www.wsj.com, December 15, 2021.

[4] “Powell speech: Inflation will run above our 2.0% goal well into next year,” www.fxstreet.com, December 15, 2021.

[5] “President's Message: Volcker's Handling of the Great Inflation Taught Us Much,” www.stlouisfed.org, January 1, 2005.

[6] “Oil Shock of 1973-74 | Federal Reserve History,” www.federalreservehistory.org, November 22, 2013.

[7] Op. cit., www.stlouisfed.org, January 1, 2005.

[8] “How Paul Volcker beat inflation and saved an independent Fed,” www.washingtonpost.com, December 10, 2019.

[9] “Netherlands starts ‘unavoidable’ Christmas COVID-19 lockdown,” www.nypost.com, December 19, 2021.